|

| Does this look like the suburbs? |

Clark Street. From Daley Plaza at the heart of the Chicago Loop, it heads north along the Gold Coast and ambles through Lincoln Park and Lakeview on the way to Wrigley Field.

This is not the suburbs.

The Clark Street corridor is a walkable urban neighborhood that we’ve been treating like sprawling suburbia—like a place to drive through rather than a place to live.

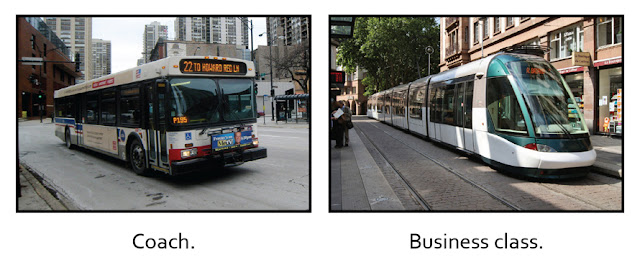

The largest unmet demand in American real estate is for walkable urbanism—neighborhoods close to downtown with high-quality (rail) transit service and lots of amenities within walking distance of home. There is plenty of demand for a few such neighborhoods in Chicago, too.

There are too many people living in the Clark Street corridor for it to be efficiently served by a transportation infrastructure that prioritizes through traffic and parking over transit and biking on every single street. What works in the more sprawling, auto-dependent neighborhoods to the west doesn’t work near the lakefront. There’s no reason we should continue to treat all of our 814 streets as though they were all the same, when they’re obviously not. There’s plenty of room for some variety in Chicago—for a few streets that prioritize pedestrians, or cyclists, or transit over cars. When it comes to streets, we could use a little more choice and competition.

The good news is that we have enough density in the Clark Street corridor to justify having one street that prioritizes commuter transit and shopping over driving and parking. It's the densest place in the city. We’re lucky to have enough density for world-class transit, for great neighborhood shopping in a pedestrian environment, and for car ownership to be an option rather than a necessity. We can spend less on car loans, gas, insurance, maintenance, and parking and more on real estate and restaurants. We could be wasting less time stuck in a car than anyone in Chicago—and spending more time at the beach or the bar, the zoo or the Cubs game, with our families and our friends.