Exit the #11

I heard Forrest Claypool speak at City Club this week, and

he did a good job of explaining the difficult and ultimately successful task of

reprioritizing, getting labor concessions, and making service cuts to balance

the CTA’s budget. One of those cuts was the #11 bus through Lincoln Park, and

it’s making a lot of people angry. Still, on the whole, it’s an impressive

achievement.

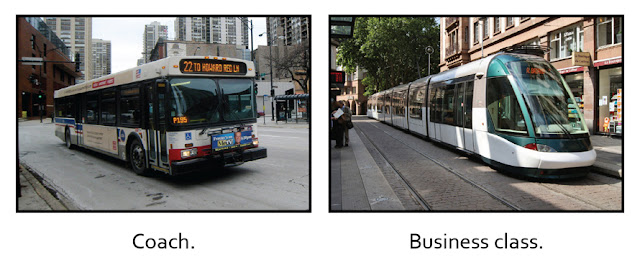

Seventy years ago, transit agencies decided buses are better

than streetcars because the routes can be added, discontinued, or redrawn at

any time. Buses are flexible. That’s a big advantage for a transit agency

that’s trying to balance its budget in the face of changing demographic trends

like urban divestment, suburban sprawl, white flight, and so forth. It’s not

the CTA’s job to make the city a better place to live, to help it attract

people from the suburbs, or outcompete other cities. The CTA is just supposed

to take people where they want to go.

If cancelling the #11 bus means a steep decline in foot

traffic on Lincoln Avenue, and businesses fail up and down the street, that’s

not the CTA’s fault. If you’re too young or too old to drive, or just too

sensible to spend $12,000 a year on a car (the average in Chicago), you’ll have

to walk to the L—but that’s not the CTA’s fault. And if Lincoln Avenue becomes

a place to drive through instead of a place to live, and that spoils the

quality of life and causes property values in the neighborhood to decline,

that’s not the CTA’s fault either.

I know Forrest Claypool cares about repopulating the vacated

parts of our city and making Chicago easier to get around in. I know he wants

to grow the economy and reduce traffic congestion. I know he cares about

helping Chicagoans reduce their household debt, waste less on driving, and

invest more in real estate or their kids’ education. I know he wants us to be

able to take transit to work so we don’t have to spend two or three hours of

every workday working to pay for the car that got us there. I know he wants to

fix all that. He just needs more tools in the toolbox.

Enter the Streetcar

Cities all over the United States are either building or

planning modern streetcar lines. For the most part, they’re not transit

projects—other cities don’t have the kind of population density and transit

ridership we do in Chicago to make their streetcars cost-effective as transit

systems. Instead, American streetcars are usually business and property

development initiatives. Everywhere they go in, they increase property values

and boost local business. They spark economic growth and urban revitalization.

Why? Because the public commitment to building streetcar

infrastructure—to putting tracks in the street—mitigates the risk for

developers and investors. It ensures that the location will retain its value

regardless of gas prices and recessions. It’s a promise of lasting convenience

and walkability for businesses and homeowners alike. That spurs and channels

growth all along the streetcar line.

For the CTA, the big advantage of the bus is flexibility.

But you don’t want flexibility if you just signed a fifteen-year lease. You

don’t want flexibility if you just bought a big apartment, thinking you could

afford it because you weren’t going to have to own, maintain, insure, fuel, and

park a car. You don’t want flexibility if you’re thinking of investing in a new

mixed-use transit-oriented development. The homeowner doesn’t want flexibility,

the developer doesn’t want flexibility, and the banker doesn’t want flexibility.

Everybody engaged in building up a neighborhood, in making it more vibrant and

convenient and fun to live in, wants reliability. Predictability.

Commitment.

The streetcar is not just about taking people where they

want to go, it’s about building strong, enduring neighborhoods.